Idea by

Rosa Rogina

Call for ideas 2021

Silent Landscapes

Silent Landscapes

- Systemic changes

While unpacking the implications of humanitarian (de)mining and land management in post-conflict territories, the project explores how can architectural theory and practice be expanded and utilised as a tool for a wider social, environmental and economic change.

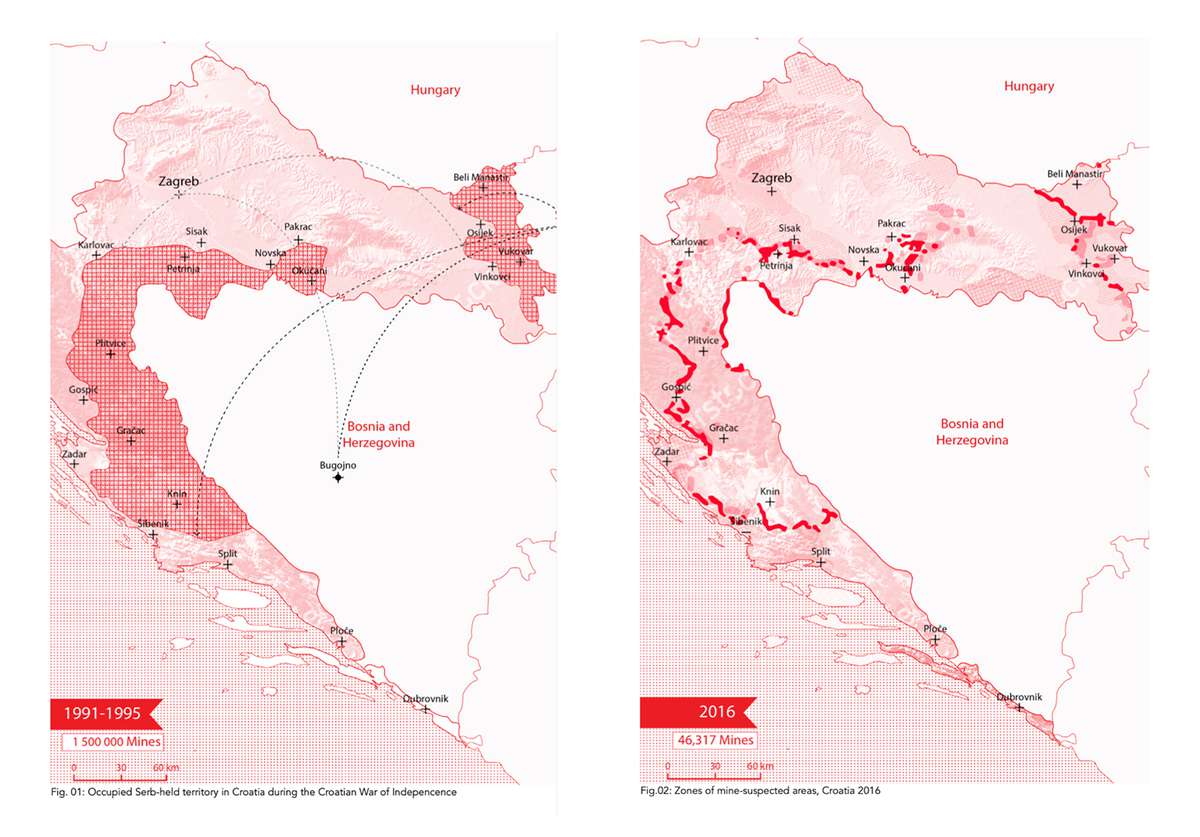

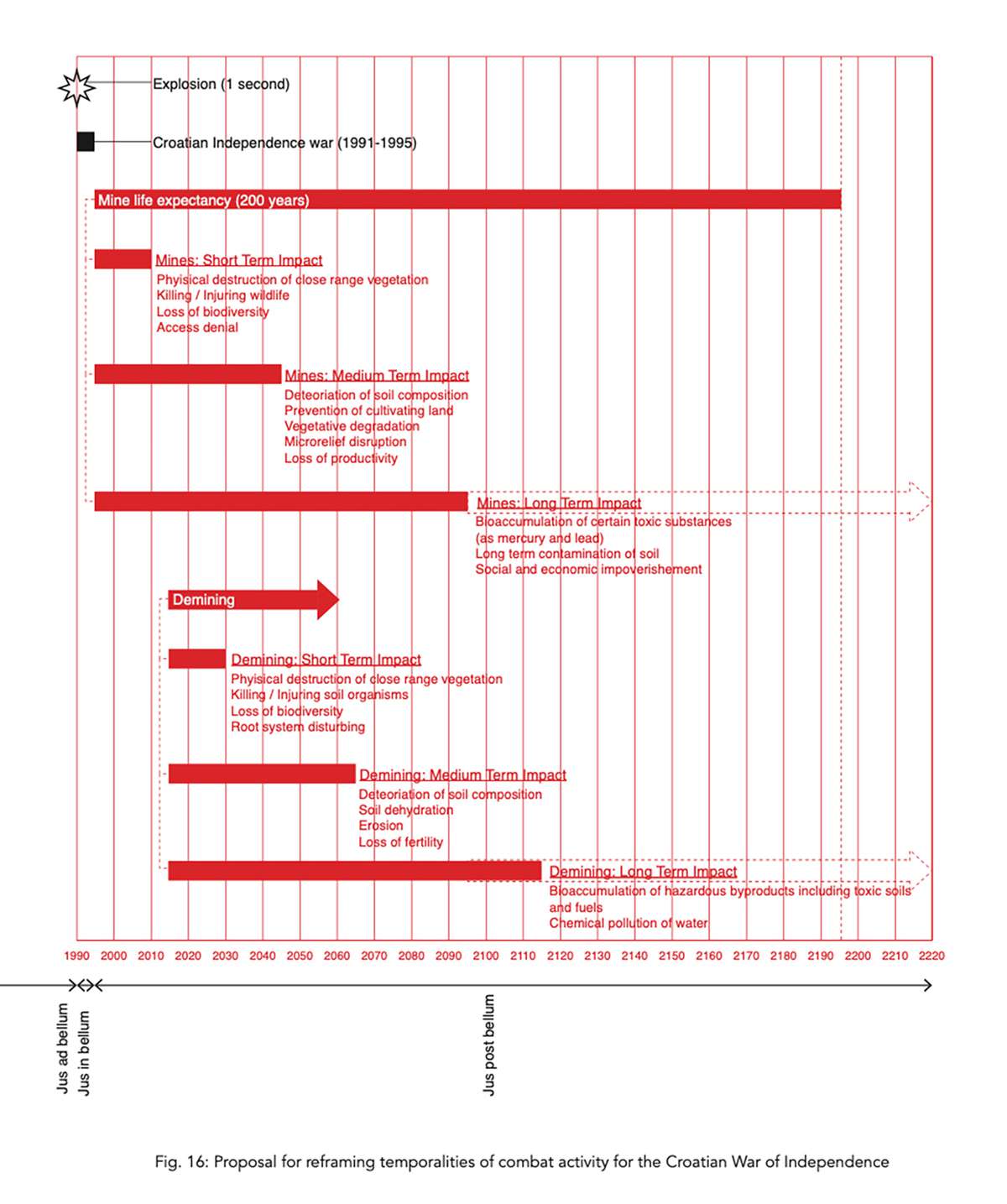

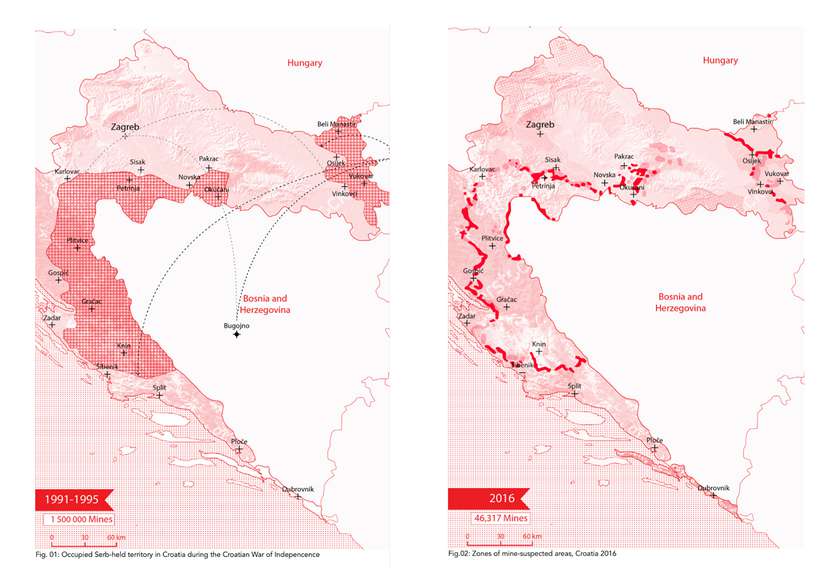

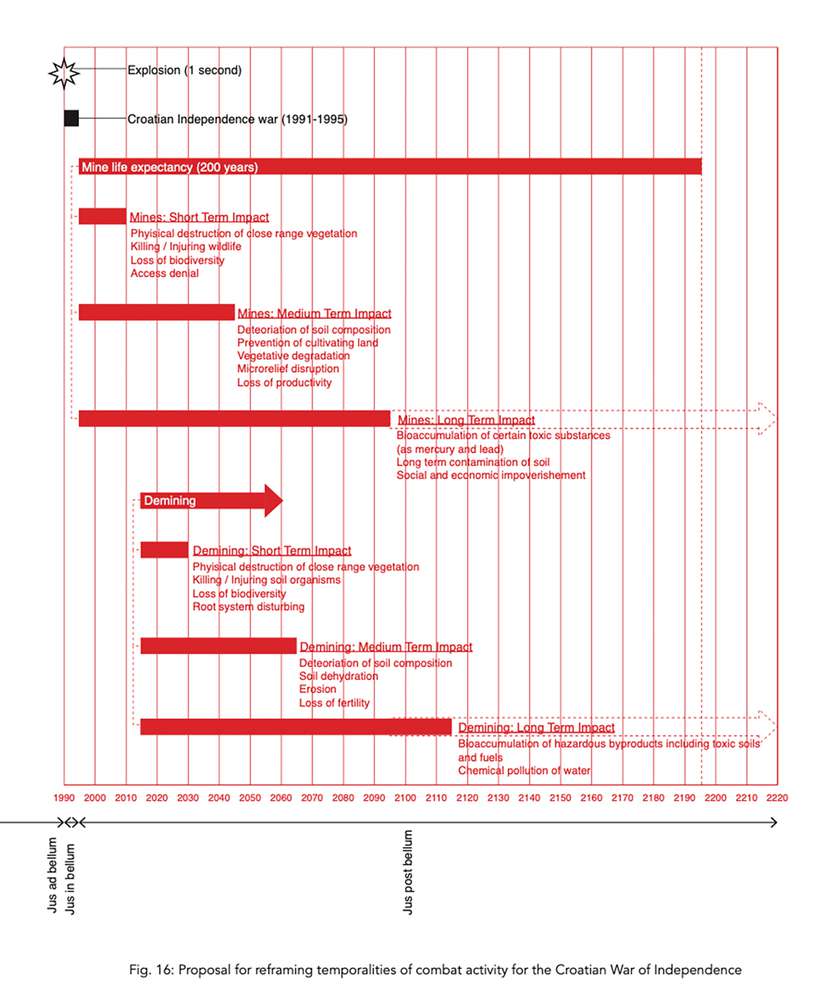

In the last 100 years, the nature of how we fight has entered an entirely new dimension in which combat violence is being exercised across various spatial and temporal scales. By investigating a linear strip of minefields near Petrinja, Croatia, the project situates the natural environment as the most endangered entity of the delayed combat violence and questions which kind of intervention in this type of post-traumatic setting is (or is not) needed. Considering the processes of landmine stagnation and clearance as an additional temporality of wartime violence against the local environment, the project draws on the emerging concept of jus post bellum to redefine and challenge the temporality of the ‘post’.

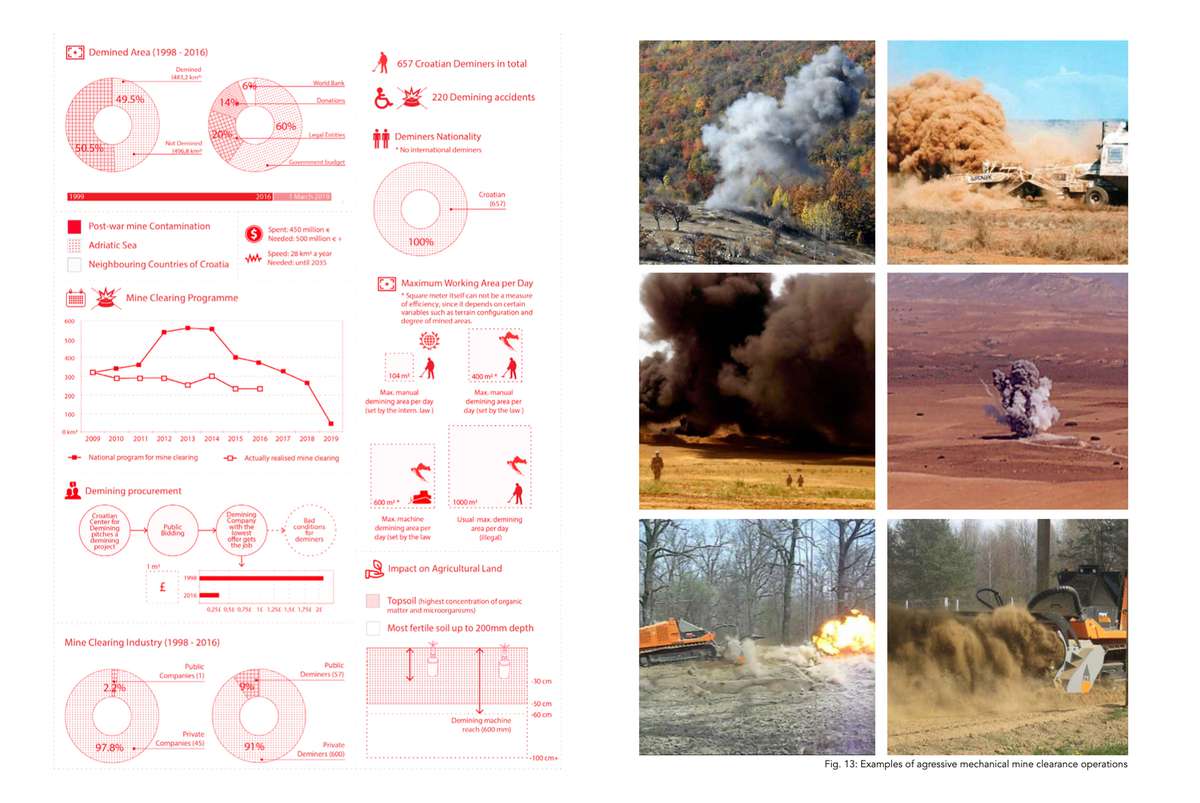

With a lifespan of 200 years, buried unexploded landmines often cause irreparable damage to local ecosystems. If one thinks of the processes of landmine stagnation and clearance as another temporality of war violence over the local environment, there is a new sense of urgency for global anti-landmine movements to situate natural environment as the most endangered entity of this particular instance of combat violence.

Landmine copies showing samples of affected natural materials collected from a local minefield, made by author

This newly configured strip of land still acts as a border, but by different means. The line that previously existed on military maps is being transformed into a scarred linear territory of unfarmed land and forests highly contaminated with landmines and other unexploded ordinances. This is a three-dimensional space with its own length, width, and depth, where different social, economic, and environmental logics meet.

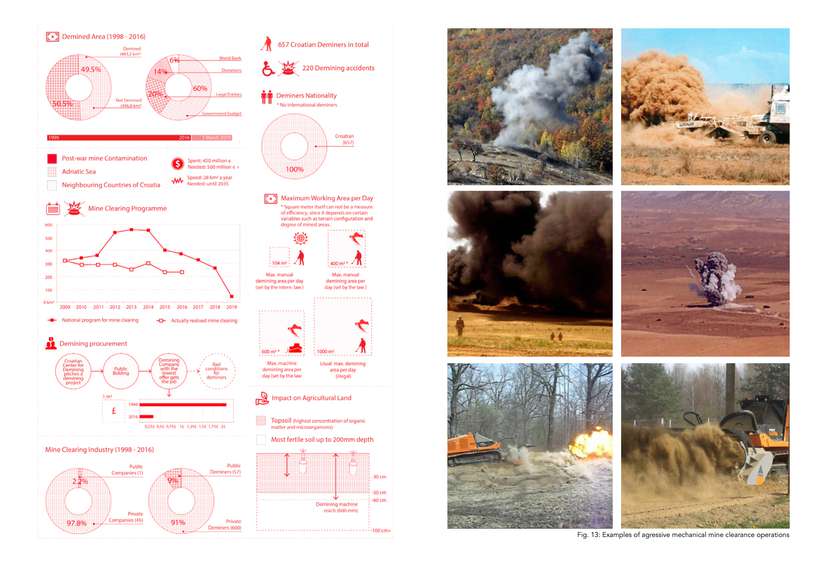

While rehabilitation and reconstruction are instinctive human reactions to any type of widespread disaster, what happens when these hostile actions hold a certain level of ambiguity and further environmental repercussions? The attempts to solve the long-lasting presence of landmines with interventions that, rather than heal, produce additional trauma to the local environment should be critically examined and its alternatives included under the relevant section of international humanitarian law.

Spatial anomalies that crystallise through the processes of landmine stagnation and post-war clearance can be used as a prism to reveal the blurred distinction between moments of war, post-war humanitarian reconstruction and peace. Jus post bellum holds the potential to start measuring the effects of human harm to its natural surroundings on the nature-centred notion of time and to reframe human relationship with nature across various extended temporalities of contemporary warfare.

Silent Landscapes

Silent Landscapes

- Systemic changes

While unpacking the implications of humanitarian (de)mining and land management in post-conflict territories, the project explores how can architectural theory and practice be expanded and utilised as a tool for a wider social, environmental and economic change.

In the last 100 years, the nature of how we fight has entered an entirely new dimension in which combat violence is being exercised across various spatial and temporal scales. By investigating a linear strip of minefields near Petrinja, Croatia, the project situates the natural environment as the most endangered entity of the delayed combat violence and questions which kind of intervention in this type of post-traumatic setting is (or is not) needed. Considering the processes of landmine stagnation and clearance as an additional temporality of wartime violence against the local environment, the project draws on the emerging concept of jus post bellum to redefine and challenge the temporality of the ‘post’.

With a lifespan of 200 years, buried unexploded landmines often cause irreparable damage to local ecosystems. If one thinks of the processes of landmine stagnation and clearance as another temporality of war violence over the local environment, there is a new sense of urgency for global anti-landmine movements to situate natural environment as the most endangered entity of this particular instance of combat violence.

Landmine copies showing samples of affected natural materials collected from a local minefield, made by author

This newly configured strip of land still acts as a border, but by different means. The line that previously existed on military maps is being transformed into a scarred linear territory of unfarmed land and forests highly contaminated with landmines and other unexploded ordinances. This is a three-dimensional space with its own length, width, and depth, where different social, economic, and environmental logics meet.

While rehabilitation and reconstruction are instinctive human reactions to any type of widespread disaster, what happens when these hostile actions hold a certain level of ambiguity and further environmental repercussions? The attempts to solve the long-lasting presence of landmines with interventions that, rather than heal, produce additional trauma to the local environment should be critically examined and its alternatives included under the relevant section of international humanitarian law.

Spatial anomalies that crystallise through the processes of landmine stagnation and post-war clearance can be used as a prism to reveal the blurred distinction between moments of war, post-war humanitarian reconstruction and peace. Jus post bellum holds the potential to start measuring the effects of human harm to its natural surroundings on the nature-centred notion of time and to reframe human relationship with nature across various extended temporalities of contemporary warfare.