Idea by

Andrew Copolov

Call for ideas 2020

Along Liquid Paths

Along Liquid Paths

- New alliances

The project explores the complex ways in which the space of the sea is organised and governed. At a macro scale this concerns discrepancies over juridical boundaries, and at the scale of the vessel it’s about systems such as ‘flags of convenience' - where shipping companies fly flags from nations like Panama or Liberia to avoid tax as well as pesky labour regulations.

Today capital is generated as much in the distribution of goods as in their production. This places the cargo ship, along with the port and the logistics centre, at the forefront of so-called ‘supply chain capitalism’. For now these sites contribute to the flattening of space in the pursuit of frictionless circulation; however if designed using the master’s tools and a little tact, these sites might help to empower the logistics workers who attend the fragile chokepoints of the global supply chain. Either way, the implications of how these sites are designed reaches far beyond the sea.

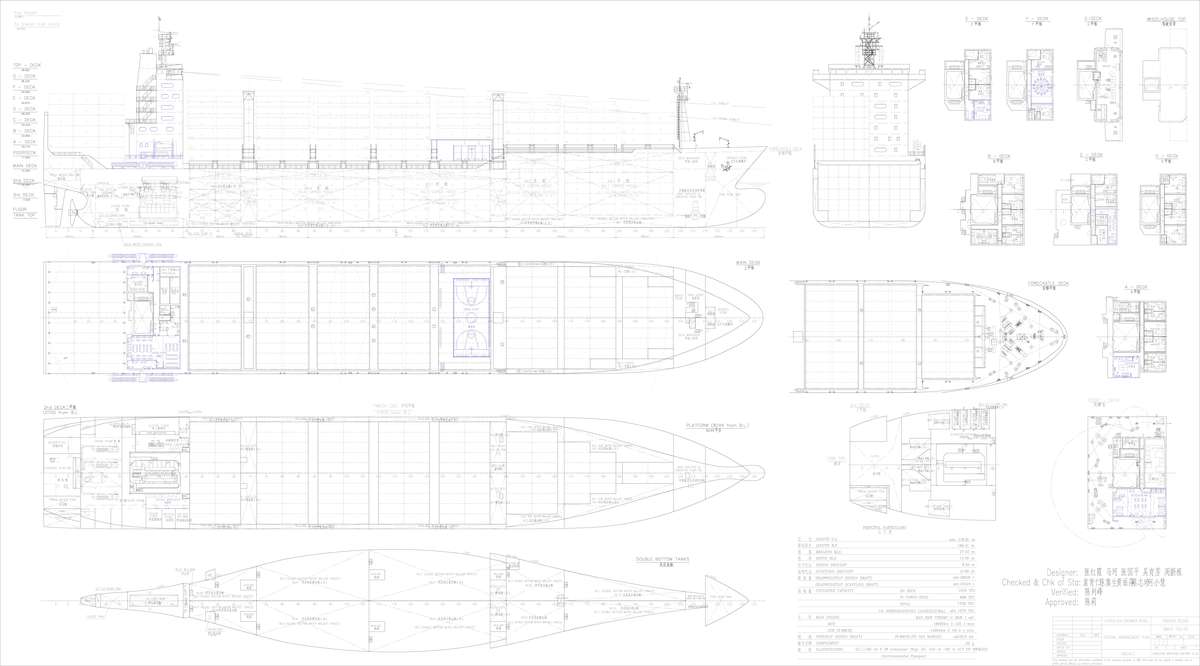

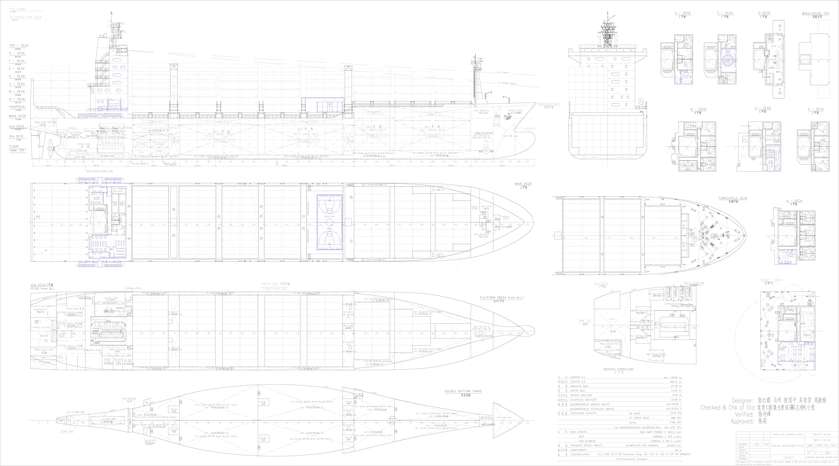

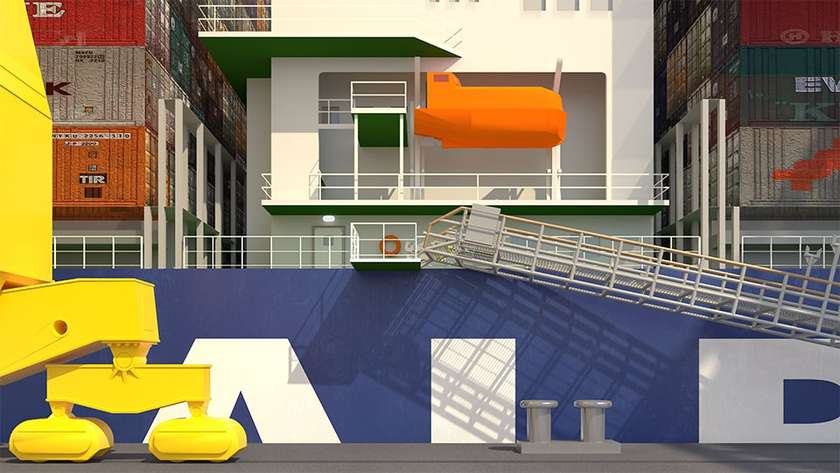

The ship is 230m long and can carry up to 5000 standard containers. But of the fraction of the ship that isn’t used for housing these containers, most of it is occupied by cabins or mechanical elements. The remaining space, shown in blue, is what has been designed. Here subtle architectural interventions emerge as a direct reflection of the cooperative model.

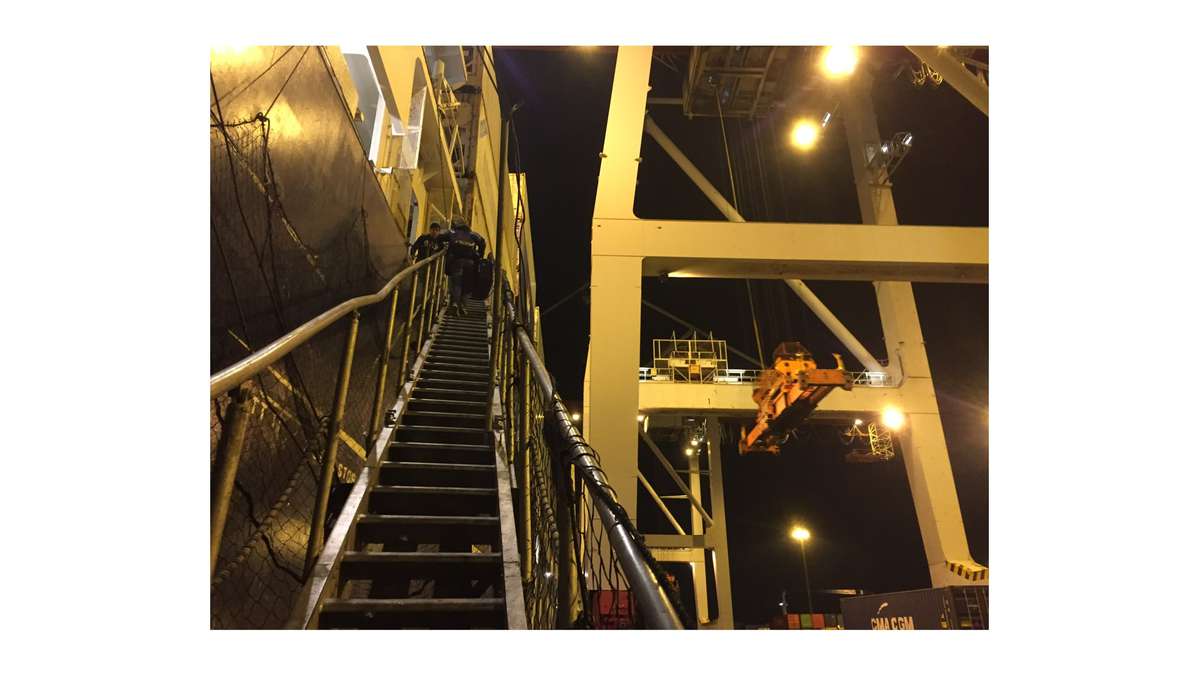

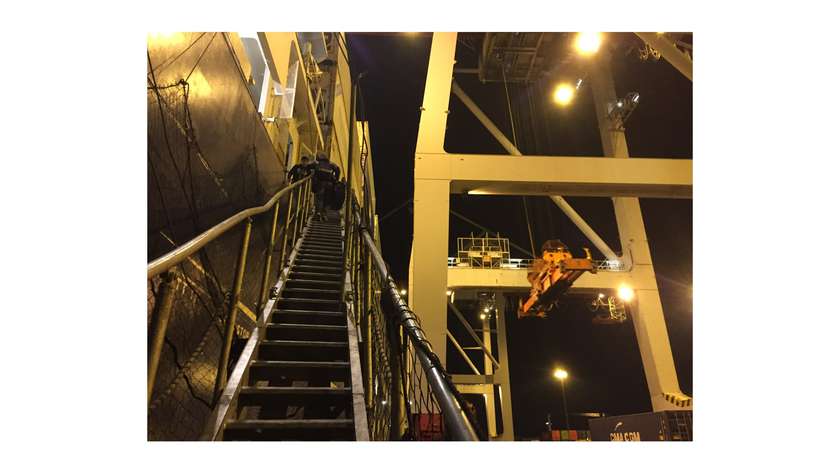

On any big ship the gangway is the first thing one encounters; it’s the bridge between the vessel and the rest of the world. The crew members say that on other ships dragging their baggage up the gangway at the start of their contract is the heaviest feeling, and going down six months later is the most joyful. But on this ship things are a little different, and the gangway is the first thing to suggest this.

"The passage had begun, and the ship, a fragment detached from the earth, went on lonely and swift like a small planet. Round her the abuses of sky and sea met in an unattainable frontier. A great circular solitude moved with her, ever changing and ever the same, always monotonous and always imposing." Joseph Conrad, The Nigger of the Narcissus

On other ships officers and crew eat in separate rooms, but here they share not only with each other but with other members of their cooperative as well. Those working on the deck hang up their oil-caked jackets and gloves in the entryway before joining strangers and fellow countrymen for a meal.

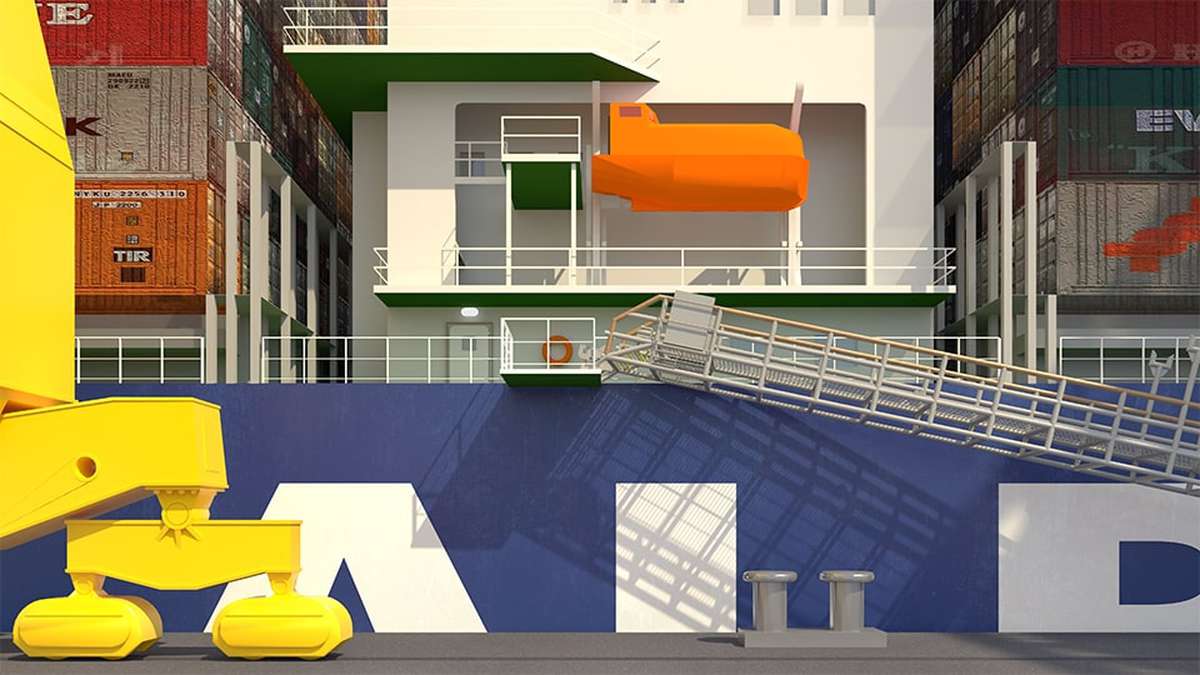

In a standard cargo ship every inch of space is squeezed for its productive potential, so for this ship to be configured in such a way that the worker is placed before the generation of profit is in itself radical. In this context something as minor as having bigger windows becomes significant.

Along Liquid Paths

Along Liquid Paths

- New alliances

The project explores the complex ways in which the space of the sea is organised and governed. At a macro scale this concerns discrepancies over juridical boundaries, and at the scale of the vessel it’s about systems such as ‘flags of convenience' - where shipping companies fly flags from nations like Panama or Liberia to avoid tax as well as pesky labour regulations.

Today capital is generated as much in the distribution of goods as in their production. This places the cargo ship, along with the port and the logistics centre, at the forefront of so-called ‘supply chain capitalism’. For now these sites contribute to the flattening of space in the pursuit of frictionless circulation; however if designed using the master’s tools and a little tact, these sites might help to empower the logistics workers who attend the fragile chokepoints of the global supply chain. Either way, the implications of how these sites are designed reaches far beyond the sea.

The ship is 230m long and can carry up to 5000 standard containers. But of the fraction of the ship that isn’t used for housing these containers, most of it is occupied by cabins or mechanical elements. The remaining space, shown in blue, is what has been designed. Here subtle architectural interventions emerge as a direct reflection of the cooperative model.

On any big ship the gangway is the first thing one encounters; it’s the bridge between the vessel and the rest of the world. The crew members say that on other ships dragging their baggage up the gangway at the start of their contract is the heaviest feeling, and going down six months later is the most joyful. But on this ship things are a little different, and the gangway is the first thing to suggest this.

"The passage had begun, and the ship, a fragment detached from the earth, went on lonely and swift like a small planet. Round her the abuses of sky and sea met in an unattainable frontier. A great circular solitude moved with her, ever changing and ever the same, always monotonous and always imposing." Joseph Conrad, The Nigger of the Narcissus

On other ships officers and crew eat in separate rooms, but here they share not only with each other but with other members of their cooperative as well. Those working on the deck hang up their oil-caked jackets and gloves in the entryway before joining strangers and fellow countrymen for a meal.

In a standard cargo ship every inch of space is squeezed for its productive potential, so for this ship to be configured in such a way that the worker is placed before the generation of profit is in itself radical. In this context something as minor as having bigger windows becomes significant.