Idea by

Diego Martín Sánchez, Noemí Gómez Lobo

furiistudio

Call for ideas 2021

Urban Forestry Practices Constructing More-than-Human Commons

Urban Forestry Practices Constructing More-than-Human Commons

- New alliances

Architecture and urbanism are facing a paradigm shift, from capitalist logics to ecological concerns. The climate crisis instigates these fields to reshape our livelihoods, imagining alternative practices that work with existing environments while rejecting the premise of infinite resources. Urban forestry can help build more-than-human commons by connecting trees and citizens. It differs greatly from conventional forestry in that its purpose is not to transform extracted wood into a commodity but to care for the metropolitan forest. Precisely because it is not an industrial productive activity, its material outcomes are often discarded as waste. However, being situated in the urban context broadens the possibilities of participation of various agents, as well as the use of resources resulting from tree maintenance. The value that underlies urban forestry is not a marketable one, but that of the relationships it creates, generating novel architectural typologies and urban networks.

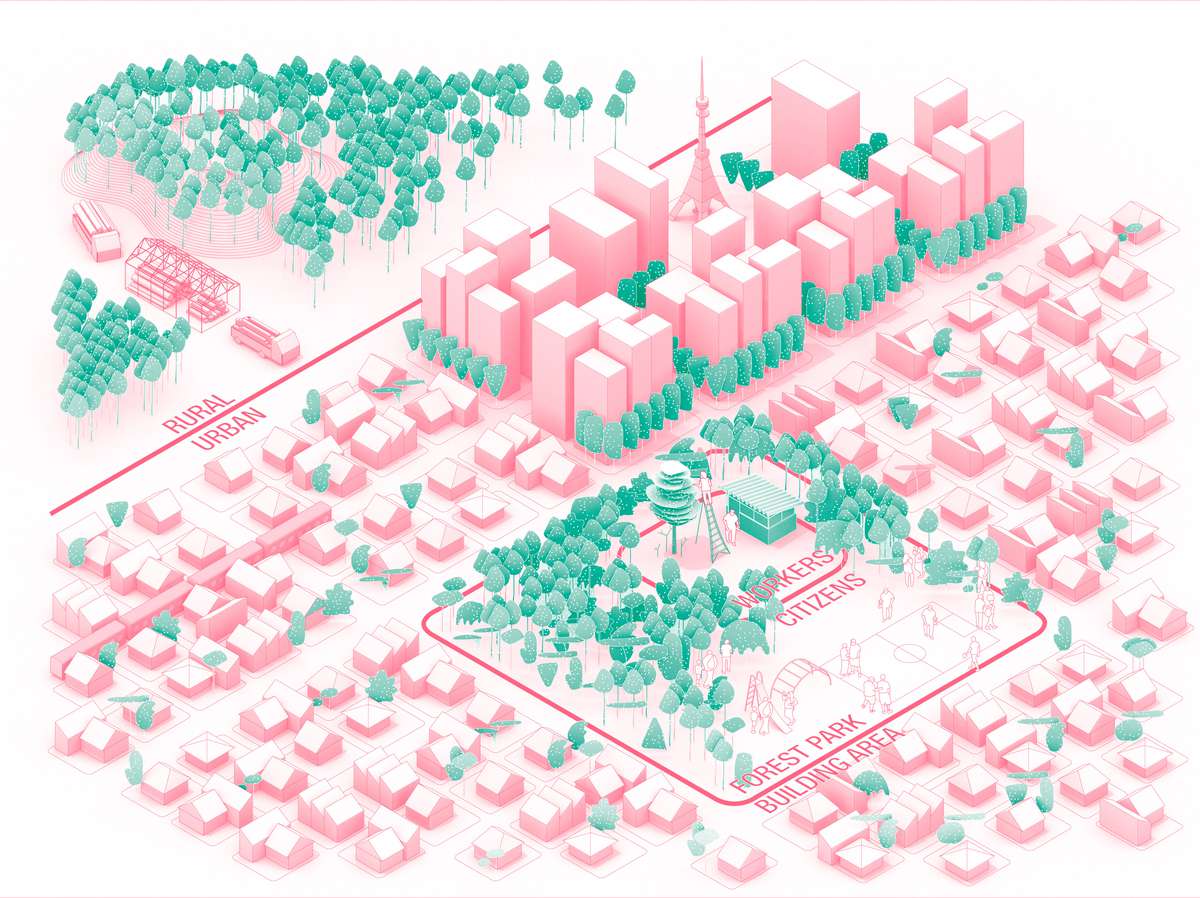

Modern cities are shaped by an epistemological duality that positions the natural against the social, leading to a series of binaries. Perhaps the strongest assumption is that of the rural against the urban, where nature in the countryside is framed as productive, while in the city it is passive. This institutionalized urban forest, which usually appears in the form of parks, is blocked to the active engagement of citizens, and tree care practices are usually carried out by professionals.

However, when thinking architecture not only within a site but also positioned in a network, it can function as a catalyst for relationships. Thus, by diversifying accessible resources and the actants involved, urban forestry emerges as a critical framework for subverting the implicit barriers with the city's natural resources, transcending binaries to understand more-than-human commons as a dynamic interaction.

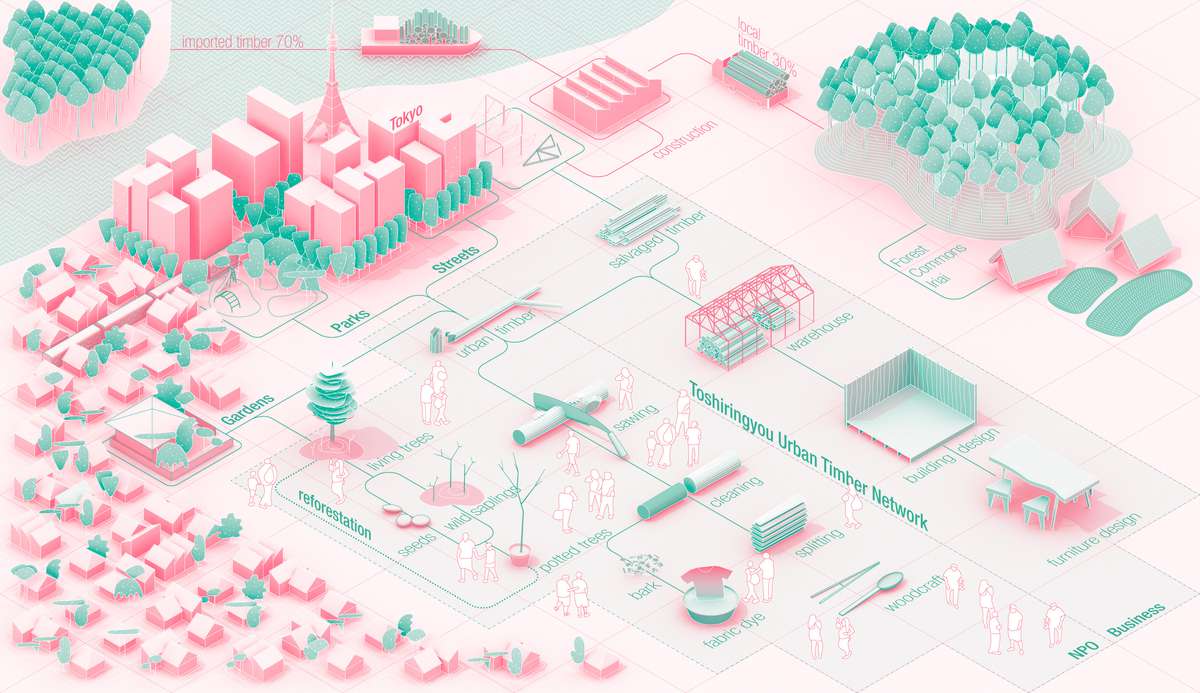

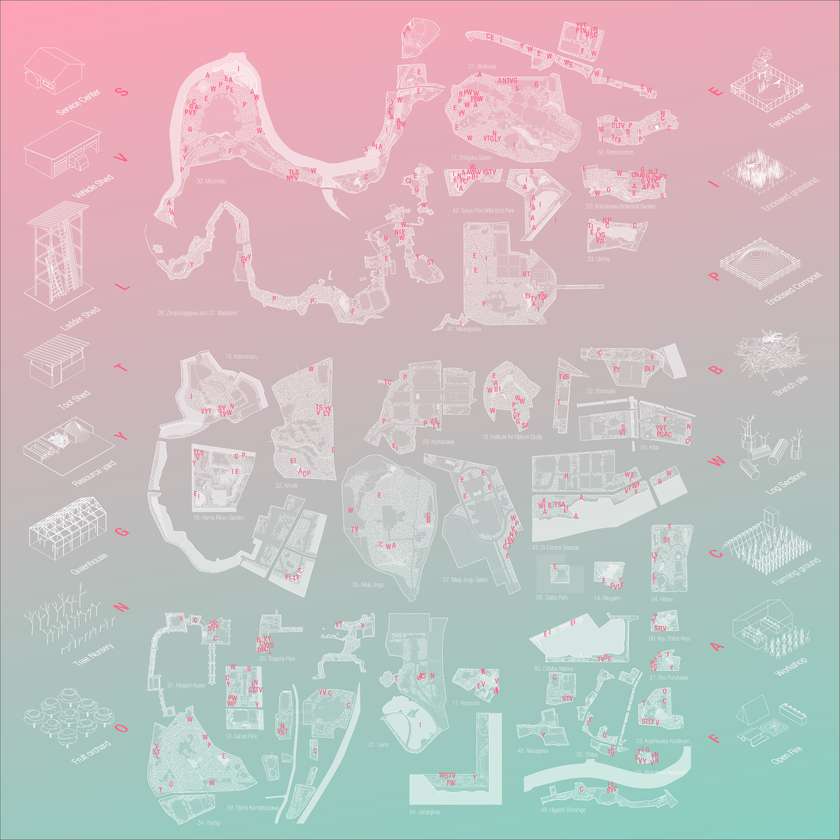

Taking as a case study a real practice of emerging urban forestry - Toshiringyou started in 2012 by an architect trained as an urban forester in Tokyo - and drawing its network, we can understand how by giving value to leftover matter it is possible to strengthen connections, diversifying resources and agents involved. These practices often use urban and salvaged timber for design projects that involve residents in wood processing workshops ranging from sawing logs to planting seeds.

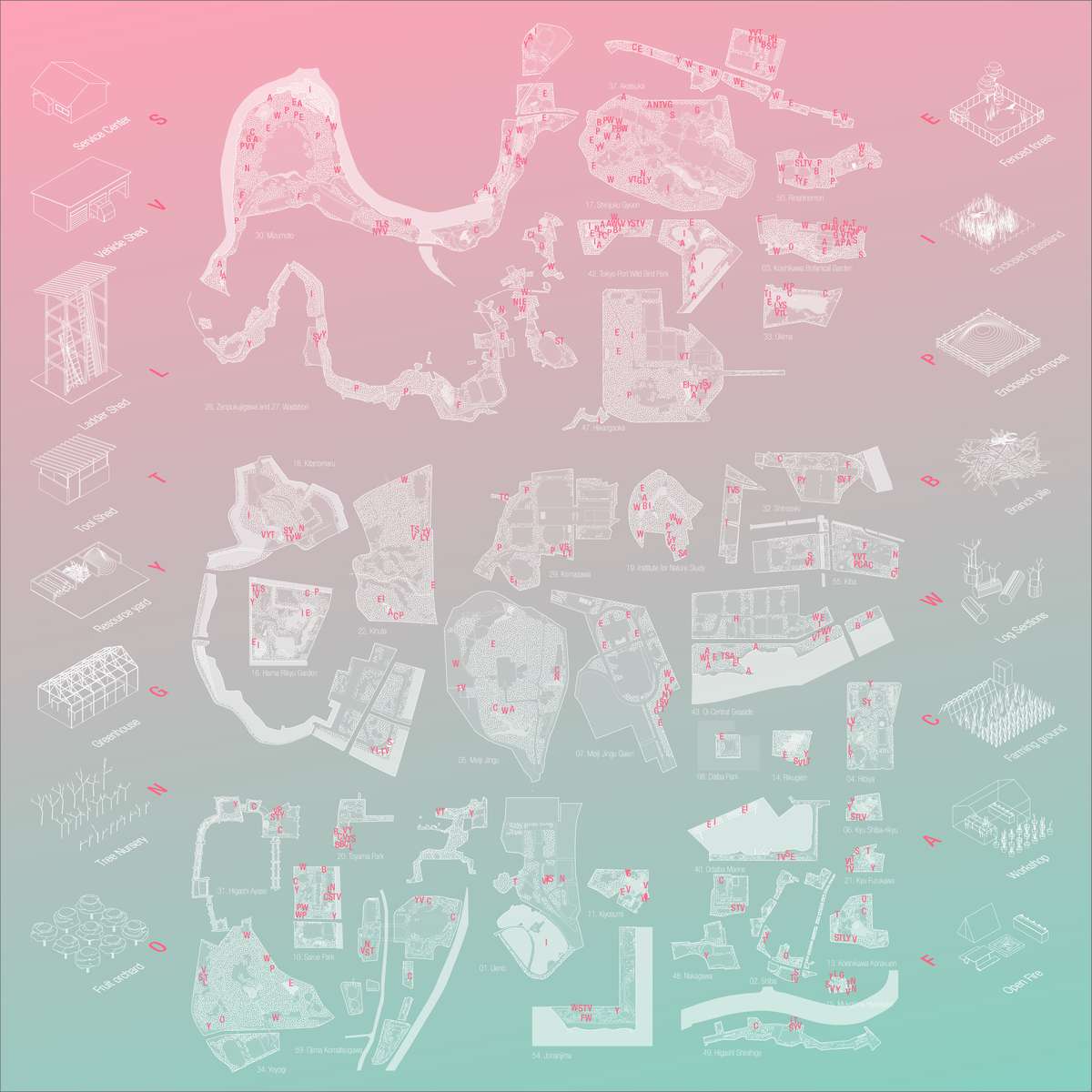

Keeping Tokyo as a case study, we can reformulate its metropolitan parks as latent sites for weaving connections through the practice of tree care. These urban forestry assemblages can reveal hidden places for maintenance as important beacons for constructing more-than-human commons in the city.

Urban Forestry Practices Constructing More-than-Human Commons

Urban Forestry Practices Constructing More-than-Human Commons

- New alliances

Architecture and urbanism are facing a paradigm shift, from capitalist logics to ecological concerns. The climate crisis instigates these fields to reshape our livelihoods, imagining alternative practices that work with existing environments while rejecting the premise of infinite resources. Urban forestry can help build more-than-human commons by connecting trees and citizens. It differs greatly from conventional forestry in that its purpose is not to transform extracted wood into a commodity but to care for the metropolitan forest. Precisely because it is not an industrial productive activity, its material outcomes are often discarded as waste. However, being situated in the urban context broadens the possibilities of participation of various agents, as well as the use of resources resulting from tree maintenance. The value that underlies urban forestry is not a marketable one, but that of the relationships it creates, generating novel architectural typologies and urban networks.

Modern cities are shaped by an epistemological duality that positions the natural against the social, leading to a series of binaries. Perhaps the strongest assumption is that of the rural against the urban, where nature in the countryside is framed as productive, while in the city it is passive. This institutionalized urban forest, which usually appears in the form of parks, is blocked to the active engagement of citizens, and tree care practices are usually carried out by professionals.

However, when thinking architecture not only within a site but also positioned in a network, it can function as a catalyst for relationships. Thus, by diversifying accessible resources and the actants involved, urban forestry emerges as a critical framework for subverting the implicit barriers with the city's natural resources, transcending binaries to understand more-than-human commons as a dynamic interaction.

Taking as a case study a real practice of emerging urban forestry - Toshiringyou started in 2012 by an architect trained as an urban forester in Tokyo - and drawing its network, we can understand how by giving value to leftover matter it is possible to strengthen connections, diversifying resources and agents involved. These practices often use urban and salvaged timber for design projects that involve residents in wood processing workshops ranging from sawing logs to planting seeds.

Keeping Tokyo as a case study, we can reformulate its metropolitan parks as latent sites for weaving connections through the practice of tree care. These urban forestry assemblages can reveal hidden places for maintenance as important beacons for constructing more-than-human commons in the city.