Inventories of Occupation

We spoke to Corales about his interest in the potential of agricultural typologies to act as active agents in the conflict between original communities and the state of Chile.

For the 2018 edition of the Venice Architecture Biennale, curated by Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara, the theme of “Freespace” was intended as a robust tool that opens up the potential for a multiplicity of nuanced translations. Whilst the idea of pairing freedom and space allows participants to address liminal, in-between spaces in search of architecture’s added value, there is a darker aspect to their dividing function, which places them within the power mechanisms of marginalisation and exclusion. Into the Conflict: Inventory for an Occupation (2017), a project by Eduardo Corales, one of the bright young talents selected from our Open Call, could aptly highlight a certain question left open in this year’s Biennale: can architects do more than represent structures of injustice?

Based in both Lisbon and Santiago de Chile, Corales spent some years at the National Monuments Council, where he was in charge of historical monuments and their cultural value. These monuments are the focal points he returns to in a series of successive independent projects involving community advocacy, austerity, local economy, environmentalism and conflict as essential elements in his practice. He believes that the key to understanding the heritage value of a city and its territory lies within the analysis of its development process. As a survey and resignification of agro-industrial architecture Into the Conflict, Inventory for an Occupation is a project that explores possibilities for integration between territories in conflict. We spoke to Corales about his interest in the potential of agricultural typologies to act as active agents in the conflict between original communities and the state of Chile.

FA Journal: What triggered your interest in the territorial conflict between native communities and the State of Chile? How did the project come about?

Eduardo Corales: Several of my projects recognise the rights of pre-existence as elements with which to work. The non-recognition of pre-existence, when it comes to the interpretation of architectural heritage, is at the root of the oldest and longest armed conflict in Chile, as well as the history that has portrayed it.

It is a conflict that has not been solved. In fact, it has worsened since the founding of the country. Particularly in a territory where current opinions and economic interests are divided and where architecture has not functioned as an active agent in the conflict between original communities and the state of Chile.

I think it is interesting to be able to confront notions of architectural and colonial heritage and new ideas relating to the appreciation of native cultures as well as the mixing between them and people of European descent (mestizos). This is key to generating integration points between cultures that are sharing a territory.

FAJ: You have said that “there is no future in architecture without a conciliatory memory between peoples in conflict”. How would you describe your approach with Into the Conflict?

EC: I am concerned with the idea of architecture functioning as a personal exercise with respect to certain issues, such as segregation, that still harm us as a society today. It is through a personal contribution, in the form of a proposal, that I seek to establish common grounds for dialogue around a conflict.

The energy involved in an architecture project requires a series of actors who necessarily need a certain degree of consensus and peace in the environment they work and live in. Without a reconciled society it is very difficult to exercise a critical and free architecture.

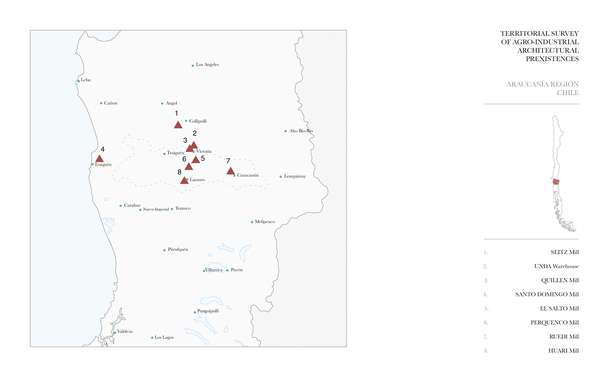

Today in the Araucanía region in Chile, there is a great deal of distance between the native peoples and the descendants of European settlers and Chileans of the region. Here there is no sense of peace, integration or fertility for the intellectual development of the society.

FAJ: Why did you decide to focus on agro-industrial architectural typology?

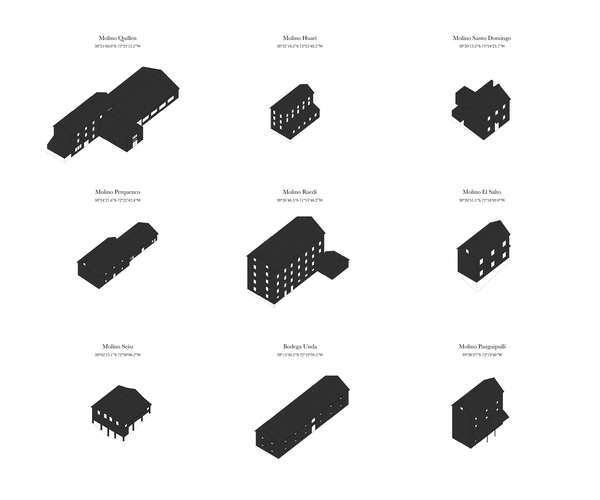

EC: I am struck by the fact that on this site of the first territorial conflict in the country, architectural symbols appear almost as pieces of territorial demarcation, such as the water mills of European origin.

The occupation of the Araucanía was brought about through weapons and agriculture. Forests and sacred territories were transformed into farmlands by military forces. The mill was the first high-rise building that appeared as a mark of progress and technology for the settlers, and as a symbol of oppression and occupation for the native peoples.

Today these mills are recognised as buildings with a heritage value. They are the heirs of a German and Swiss wood typological construction culture. As such their architectural values stand out, but they are never described as conflicted and ambiguous elements in their historical interpretation.

I am mainly interested in the versatility of use in agro-industrial architecture as a device for integration between two cultures that are distant today.

FAJ: How do you see the impact of your project among the native Mapuche people of Chile? What sort of encounters has it generated?

EC: I would like the project to generate a neutral terrain in which there is exposure of knowledge with respect to both peoples that inhabit the territory today. It is obvious that this will not be generated by an architecture project but public policy and the will of society, but I think there is a symbolic value in reinterpreting – and questioning – the role of agro-industrial heritage in the region with a viewpoint that includes people excluded from decisions on a historical level. We have undoubtedly much to learn from them.

FAJ: What do you hope to achieve with this project and what are your future plans?

EC: The project was designed with three main objectives: register, project and articulate.

The registry is related to generating an inventory of agro-industrial instances in the region and being able to access this information using the tools of architecture and history.

Once we have this information, I am interested in rethinking the possibility of reprograming these industrial architectural elements from another perspective, and the possibility of interpreting them through specific modifications. It is also interesting to be able to question the architectural values of these buildings and to test the institutional position regarding their conception of heritage.

Finally –and this is the most important – we want to allow the different actors involved in the project: the Mapuche community, Chileans living in the region, historians, academics and political authorities (both local and native) to articulate their views. I believe it is vital to advance these initiatives because – although they do not solve the problem – they can at least create possibilities to establish a critical distance necessary for dialogue.

Currently I’m working on projects that involve surveying and creating an inventory of industrial heritage architectures in Portugal and I am using this material as starting point to teach about their values and future options for reuse.

I see these kinds of methodological exercises in a multi-level dialogue with a rich industrial history as a way of using their stories as a powerful tool to integrate neighbourhoods, cities and territories.

Further reading

Read more about navigating the future of architecture in Archifutures Vol. 4: Thresholds

Or buy a copy here.