I’d Still Rather Not

In recent decades the figure of a reluctant architect has emerged: instead of strictly controlling the process of building from the drawing board to the end of construction, architects started to voluntarily retreat from it.

This retreat might be taken as a sort of experiment in self-restraint, a reaction to contemporary doubt about anthropocentric domination or as a capitulation of professional autonomy in the face of the authority of the market as the exclusive arbiter of every contemporary relationship. The final stage of architectural reluctance seems to be a Bartlebian architect – a creator that renounces the act of creation altogether and is instead preoccupied with the articulation of an architectural “I would prefer not to”.

Instead of the more conventional question of what architects actually do, it is becoming more and more relevant, then, to ask: what architects chose not to do. This would mean an exploration of what has gone missing from the architect’s working process and why the figure of a passive architect – an oxymoron only decades ago – has become so appealing in the world of today. Counter-intuitively, this would also open up a new field of the radical potential of architectural passivity: perhaps the truly disruptive act in the contemporary society of total participation is linked not to the question of how to participate (even if critically), but how not to participate. Whereas today the classical critical position has lost its radical potency and only seems to reinforce the status quo, architectural passivity perhaps offers us a chance to rethink the pejorative undertone it possesses. Perhaps passivity is always despised precisely because it offers the most radical chance of dissent.

I claim that in order to understand the contemporary possibilities of critique, the dichotomy between the ruling discourse and its conventional, oppositional, critique is insufficient and, furthermore, misleading. Instead I propose another dichotomy, one between activity and passivity. In such a dichotomy, both the ruling discourse and its critique are positioned in the “active” half – they are mutually dependent on each other and rely on each other for mutual legitimation. The other half is the “passive” half that can be further divided into affirmative passiveness (of which over-identification with its renunciation of individual identity, tendency to merge or over-identify with the ruling discourse without ironic distance and tendency to self-abolish are the clearest examples) and rejective passiveness (of which a Bartlebian position with its “I would prefer not to” would be the clearest example). This dichotomy could perhaps alternatively be understood as a parallel to Berthold Brecht’s Jasager (He Who Says Yes) and Neinsager (He Who Says No).

But what does this mean for architecture? After all, it seems that, as Ines Weizman tells us, “architecture is perhaps the least likely of practices to articulate a dissident position.”[1] It is here that the concept of over-identification becomes truly interesting for architecture. Let us focus on exploring the possibility of critically operating in architecture through what appears to be passive means: through over-identification. On one hand, over-identification seems to be the ultimate “active” position, but from the critical point of view, it represents a seemingly total renunciation of individuality, creativity and professional autonomy: a sort of renunciation of some of the basic principles of architecture, while still practicing architecture. For this we would need to relativise the well-known classical critical position that architecture is structurally incapable of operating critically, as formulated by Manfredo Tafuri: “To search for an alternative within the structures that condition the very character of architectural design is indeed an obvious contradiction in terms.”[2] Indeed, the obviousness is such that it begs questioning.

The alternative within the structure of the existing condition is, conversely, precisely what I claim can be thought of through the concept of over-identification. Another famous quote, this time by Michel Foucault, serves us well in repositioning the subject of the research into over-identification: “We need to escape the dilemma of being either for or against. One can, after all, be face to face and upright. Working with a government doesn’t imply either a subjection or a blanket acceptance. One can work and be intransigent at the same time. I would even say that the two things go together.”[3] Therefore I will try to follow the challenge posed by Judith Butler – herself following Foucault – of searching for an act of appropriation, which “may involve an alteration of power such that the power assumed or appropriated works against the power that made that assumption possible.”[4]

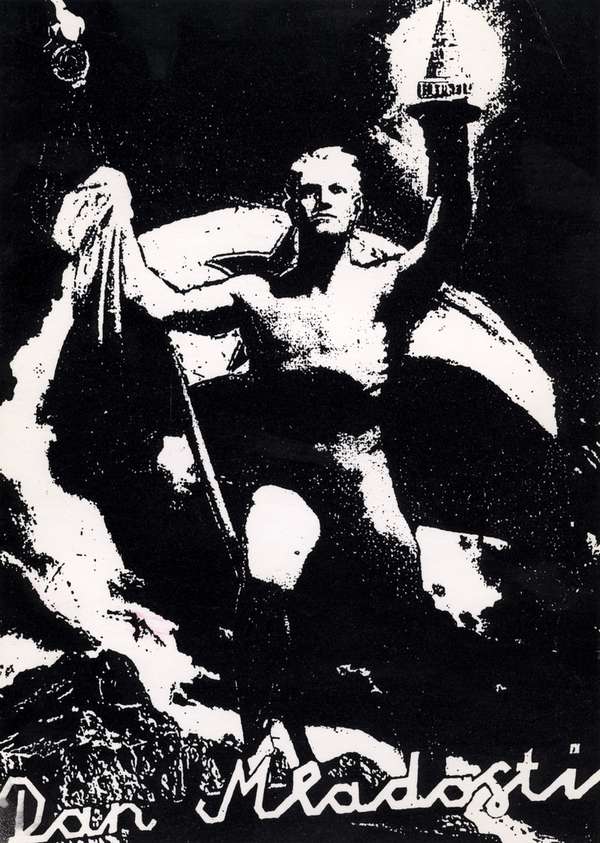

Theoretical speculations trigger a wish for a concrete architectural one. Here is one fragmented and largely visual intuitive speculation. The concept of over-identification is exemplified by the 1987 “Poster Affair” (see fig. 2) stirred up by the Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK) art collective, who were heavily criticised for using totalitarian and Nazi art imagery in their work. But what most critics missed was the fact that not so much the provocative poster itself but the many public reactions to it were the true object of NSK’s art. The official reactions were at first almost exclusively enthusiastic and only later, when the visual references of the poster were revealed to date to the 1930’s Nazi era, did they completely reverse into official condemnation. In retrospect, NSK’s act turns out to be not so much an active provocation but a passive confrontation of the, by then, socially regressive regime with its own mirror image. In the aftermath of the affair, the concept of over-identification was formulated through the writings of Slavoj Žižek and other theorists defending the NSK from accusations of fascism. Over-identification has, in recent decades, experienced a resurgence in the segments of theory and art practices that attempt to overcome effectiveness constraints on engaged art. It is as yet unclear to what extent over-identification occurs as a critical architectural technique, especially since its signatory elements are the renunciation of individuality and creativity – it strives towards seamless fusion with the prevailing (ruling) discourse via over identifying with it, subverting the ruling discourse in the process.

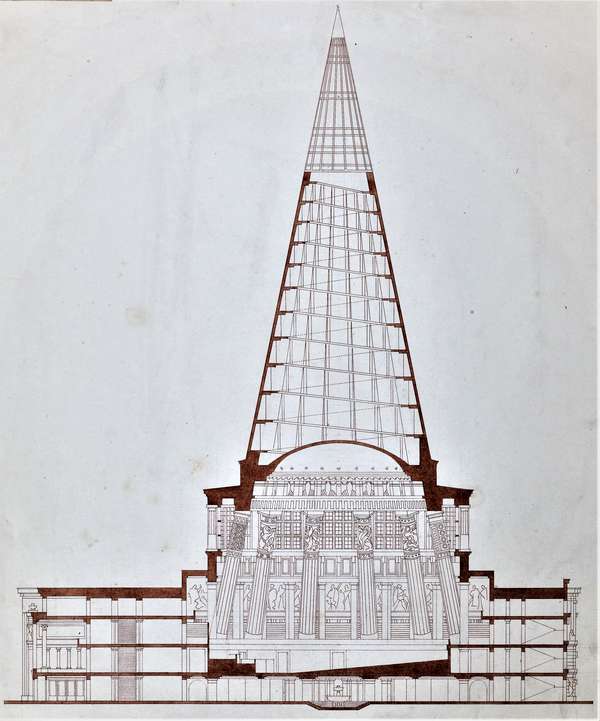

Could one of the architectural obsessions of the NSK perhaps be taken as an attempt at architectural over-identification? The unrealised project for the Slovene Parliament designed by architect Jože Plečnik in 1947 has become one of the central cultural objects of interpretation by the NSK collective throughout its existence. Analysis of the post-1990 proliferation of this unbuilt project in public, professional and political discourses outside of the sphere of NSK, especially as a utopian expression of Slovene statehood, seems to suggest that the ways in which the NSK have treated, rearticulated and used the original Plečnik project were key to its later acceptance and popularisation.

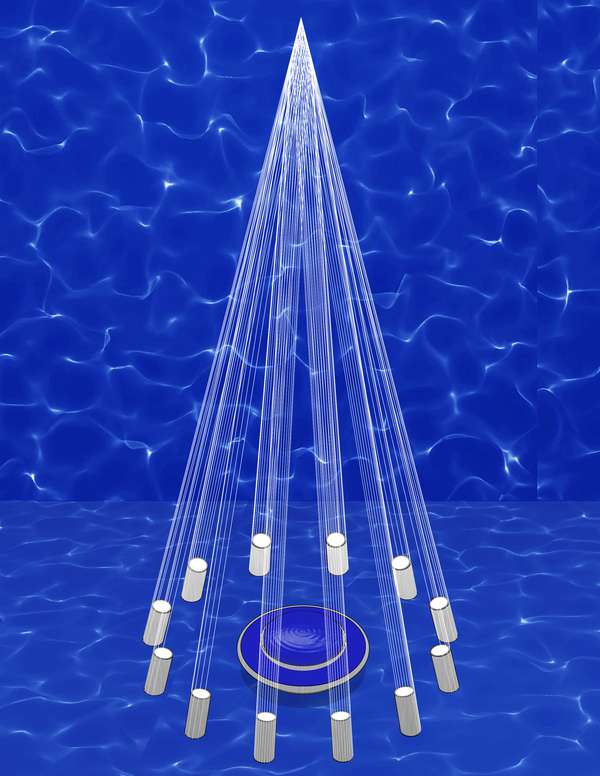

The very latest reincarnation or reinterpretation of the Plečnik Parliament building will be unveiled on May 24, 2018 in the Slovenian Pavilion at the Venice Architectural Biennial. Such an historical reappraisal of over-identification in relation to architecture strives to understand the contemporary critical alternatives left open to the architect in the paralysis of post-critical reality. Because of its elusive character, one that strives towards invisibility and containment within the ruling discourse, (successful) over-identification is clandestine and difficult to detect; conversely, the Poster Affair and other over-identification events seem to point towards a genuinely effective alternative to conventional critical activism and practices that have been criticised for being easily neutralised within the contemporary pluralist paradigm.

-

[1]

Ines Weizman ed., Architecture and the Paradox of Dissidence, Routledge (2004)

-

[2]

Quoted in: J. Rendall, J. Hill, M. Dorrian, M.Fraser, Critical Architecture,Routledge (2007)

-

[3]

Michel Foucault, Power: Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954-1984, vol. 3, 3rd ed. Harmondsworth: Penguin (2002)

-

[4]

Quoted in: Ines Weizman ed., Architecture and the Paradox of Dissidence,Routledge (2004)

Further Reading

Read another essay by Miloš Kosec, “Ruincarnations: The potential of ruins or the ruin of potential” in Archifutures Vol. 2: The Studio.