The Janus Moment

How can you navigate towards something when there are no fixed points, when you cannot determine your position? How do you know where to go, or even know when you have got there?

The Future Architecture platform and the Archifutures book series that accompanies it were set in place to address “ideas about the future of cities and architecture”. The fourth volume in this series of “field guides”, entitled “Thresholds: A field guide to navigation the future of architecture”, edited by &beyond, aims to interrogate ideas of the “future” in the context of how a growing shift in perception of the temporal context could affect architecture – along with everything else.

Architecture is traditionally considered to be a future-oriented activity. We talk about “building for the future” as if it is some kind of better place than now. And yes, future solutions, architectural or otherwise, need to be contextually appropriate, but which context are we talking about when we talk about the “future”? Which way are we looking? Are we looking at the context of now or the context of how it was or is going to be? Where is the future? We tend to think of it being ahead of us somewhere at the end of a single path marked by obstacles or gateways along the way. But, as social theorist Franco Berardi suggests, perhaps the future no longer exists, perhaps it died along with the socialist project, with modernism, at the hands of growth and capitalism. If that is the case, then we are now experiencing a post-future condition.

We are at a threshold moment where the majority of us are still operating within old linear parameters that are defined by the idols of growth, money and the accumulation of things. The time has come to step back from a growth-governed linear interpretation of time, which defines “the future” as our prescribed destination. There is a growing sense of urgency for us to grasp this threshold moment and embrace the expanding complexity of the contemporary world, opening ourselves up to the opportunities that ever-increasing furcations might bring, but this would also mean that we would have to embrace indeterminacy and uncertainty; for which we would likely need more time and more space precisely at the moment when time and space appear to be in short supply.

We can consider our current state as one where we have to look in all directions at once. It is a many-faced Janus moment where a 360° view in time and space is required at all times in order to negotiate all the thresholds and furcating paths of a now that includes tomorrow and yesterday. We need to build context-appropriate buildings, connected buildings, recyclable buildings, making use and re-use of materials and even rediscover ancient solutions. We also need to upgrade the structures and systems we have: adapting them to improve functionality in a time of rapidly changing technological context. And at the same time we need to indulge in some pretty extreme speculations in order to try and find new ways for surviving the “future”, which is, as Marc Augé says, actually now. There is no point searching for the perfect system, the perfect world, whilst knowing that it is neither possible nor, ultimately, desirable. The “future” is not a destination. The perfect world is actually the one we have right now: one that can be made better, can be changed.

So what if, instead of attempting to forge forwards, we embraced this moment by giving more consideration, time and value to the labour conditions of construction workers, for example, or the balance of inner city communities, and the effects that billions of small everyday decisions have on a global scale, the true value of non-fictional commodities, notions of the nation state, the conservative efficiency of water, transport, food and other systems, and so on. In order to open up opportunity we need to learn from the past, update the present and speculate for the future and we need to do all of this at the same time.

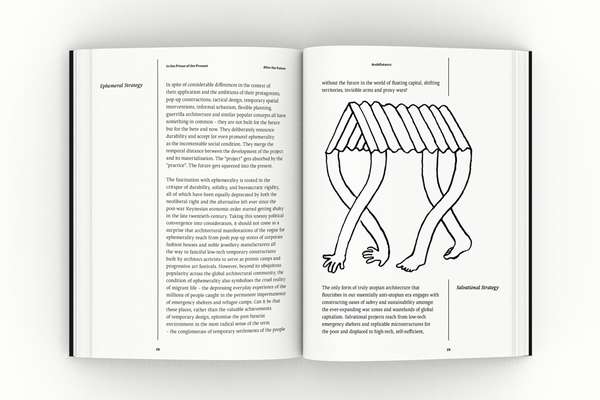

How should architects respond to such challenges? Archifutures Vol. 4 combines the voices of those already established writing and working in the “field” with projects from young practitioners submitted to the Future Architecture platform. The book’s structure is divided into sections, each addressing a different aspect of scale and area of focus. Architecture theorist Ana Jeinić kicks off with section 1: After the Present, by expanding her essay on “architecture after the future” in Archifutures Vol. 2 with a collection of “post-futurist design strategies” that lead the focus away from “ahead” and the “future”, towards looking around at social conditions. In section 2: Taxonomies, ArchDaily’s James Taylor-Foster addresses shifting rules of labels and categorisation in a fascinating conversation with Mariabruna Fabrizi and Fosco Lucarelli of SOCKS.

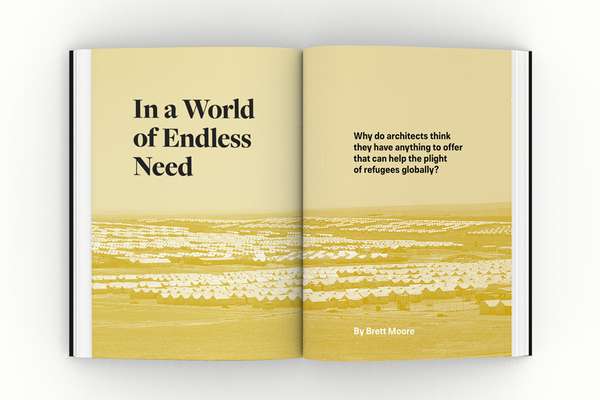

Opening section 3: Territiories, architect Nora Akawi, a specialist in borderlands, forced migration and human rights and teacher at Columbia University, tackles the tricky issues of conditions related to shifting physical borders and territories. This is followed by projects from Giuditta Vendrame and José Tomás Pérez Valle with interesting approaches to aquatic border issues. For section 4: Postnationalism, Paolo Patelli and Benedikt Stoll’s dialogue about the post-national condition and the “European dream” leads us from the EU’s identity and branding to the “Jungle” in Calais. This is closely followed, in section 4: Refuge, by a wake-up call from someone whose job it is to house millions every year: architect Brett Moore, head of Shelter and Settlements at UNHCR, issues a sharp demand for the profession to step down from its ivory towers and “regain an ethical approach and focus on humanity”. An approach that the projects from young graduates Nikita Gyawali and Marta Fernández Cortés strive to achieve.

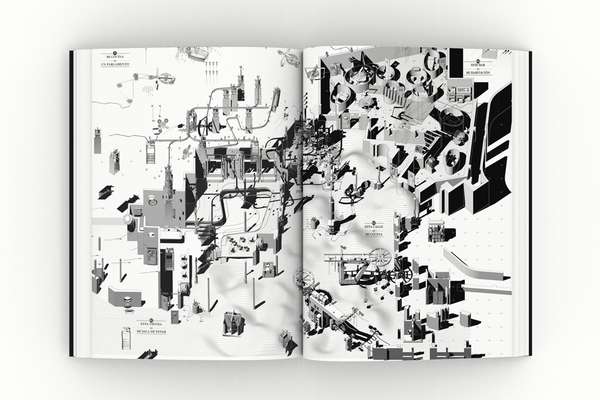

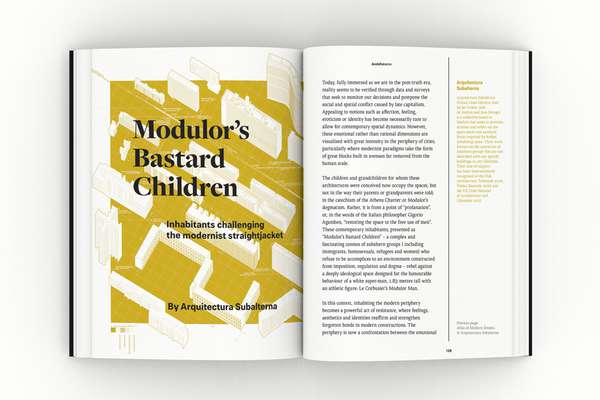

In section 6: The Human Element, Arquitectura Subalterna and Blanca Pujals take us to the scale of the individual human body with projects about escaping the dogmatic modernist straightjacket and typological archetypes respectively. At the neighbourhood level, our three-way interview about three very different approaches to European urban strategies from Filipe Estrela and Sara Neves (estrela neves, Portugal), Ilirjana Haxhiaj and Jeta Bejtullahu (Albania) and Holly Lewis and Oliver Goodhall (We Made That, UK) shows how much space (and necessity) there is for a multitude of methods to address a multitude of conditions. The days of “one hat fits all” solutions are well and truly over. In section 7: New Urban Resilience, Pedro Pitarch’s wonderfully detailed drawings of speculative metropolitan islands and Florian Bengert’s logistic landscapes emphasise the ever-present need for dreamers in this multiplicity of the contemporary urban equation.

We end the volume with section 8: Action Within Complexity and an essay by the highly respected design activist John Thackara, who, with his holistic, hands-on approach, provides a very practical set of strategic intervention examples that together allow us to begin to act within all this complexity when we stop talking about the “urban” and rural” and consider ourselves as part of a delicate and intricate bioregional balance.

Over the coming year (2018), the FA Journal will be featuring a number of articles and essays that can be considered as further reading along the thresholds theme. It will include films, projects and stories selected from the FA platform call for ideas as well as interesting articles and from protagonists in other disciplines and our publishing colleagues. Happy reading!

Further reading

Read more about navigating the future of architecture in Archifutures Vol. 4: Thresholds

Or buy a copy here.