Activate Modern Ruins

In an article Dimitris Grozopoulos, Effie Kasimati and Fani Kostourou explore the rehabilitation potential of declined buildings and abandoned cities - the modern ruins.

The project ‘Activate Modern Ruins’ is an on-going1 investigation of urban decay and modern ruins through a series of different approaches varying from photographic documentation2 and urban exploration to theoretical texts, academic research and speculative projects. Our thesis is that the modern ruins of declined buildings and abandoned cities inherently carry the imminent potential to be rehabilitated; turned into something other than mere reminders of the past. We argue that this rehabilitation can be more inclusive, sustainable and equitable when being the result of a longer-term process of collaboration and negotiation between different social groups and stakeholders.

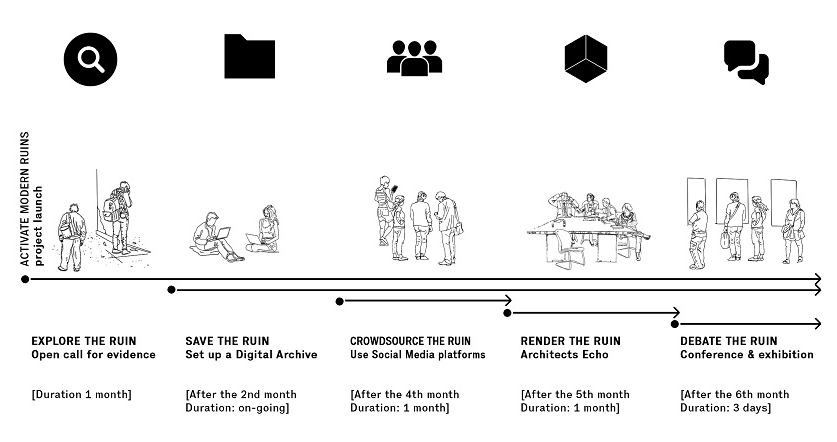

Activate Modern Ruins: 5 steps (image Dimitris Grozopoulos, Effie Kasimati and Fani Kostourou)

Activate Modern Ruins: 5 steps (image Dimitris Grozopoulos, Effie Kasimati and Fani Kostourou)

An explanatory approach to modern ruins

Throughout the history, the notion of ruin has changed dramatically. During Renaissance, the ruin was perceived as a fragmented scripted text of the antiquity. Especially the classical ruins, monuments, tombs and columns (…) ‘composed in themselves a kind of script made of gesture, line, and ornament’3. In the 18th century, Romanticism aestheticized the ruin particularly through the theories of sublime and picturesque. The artists perceived the concept and the image of the ruin as an outcome of a natural disaster or a catastrophe, ‘emblematic of the cycle of life and death, symbolic of the inevitability of life passing’.4 Later, in the 20th century the ruin was conceptualized as the great battle between nature and civilization. In his essay Simmel described architecture as ‘the only art in which the great struggle between the will of the spirit and the necessity of nature issues into real peace, in which the soul in its upward striving and nature in its gravity are held in balance’ while in the ruin ‘nature begins to have the upper hand’.5 Then, during the 21st century and alongside the rapid urban transformations, the established concepts changed radically to create new terminologies and advance existing architectural debates. Scholars started focusing on the modern ruin looking at both its tangible and intangible aspects. They discussed it in the context of architectural heritage nostalgia6, trauma7 and collective memory.8 For the modern ruin is more vulnerable than the ancient one.9 On the one hand, ruins of antiquity are frozen in time, beautified and used as touristic destinations transformed through a process of de-ruination10 into attractions. They only look doomed anymore, while the modern ruins are.9 On the other hand, modern ruins still evoked a mixture of emotions, symbolisms and memories along with a sense of melancholy for the loss of the prosperity and security of the recent past years. As Huyssen11 wrote, ‘we are nostalgic for the ruins of modernity because they still seem to hold a promise that has vanished from our own age: the promise of an alternative future’.

%20(630%20x%20840).jpg)

Abandoned Xenia Hotel, Greece (image: authors' personal archive)

Of course, modern ruins are not limited to ruins of modernity, but refer to ruins of the recent past since the 19th century. But even within this timeframe, it is difficult to classify modern ruins due to considerable variations in terms of past use, scale, historical context, cause and temporality of ruination. For example, the nuclear city of Pripyat (Ukraine) was evacuated all-at-once after the Chernobyl disaster, the Teufelsberg Nazi-facility in West Berlin (Germany) became gradually obsolete after the end of Cold War, and the residents of Spinalonga island off the Crete mainland (Greece) left in turns when the cure for leprosy was discovered.

%20(840%20x%20630)_kwh9vBv.jpg) Evacuated Pripyat (image: Clay Gilliland)

Evacuated Pripyat (image: Clay Gilliland)

However, Harbison12 was right saying that ‘ruins are not a type, but a condition’. Hence and for the purposes of this project, we define modern ruins as those recently constructed buildings, infrastructures and cities, which have been abandoned through the process of urban decay, and are currently without any use or function. In most of these cases, obsolescence has resulted from shifts in the socio-economic paradigm such as deindustrialization, or non-natural disasters like a nuclear explosion. Still, this definition leads to a rather diverse compilation of modern ruins. Only in Europe, a ruin-lover and urban explorer can talk about ‘ghost towns’ such as Sesena (Spain), Craco (Italy) and Pripyat (Ukraine), abandoned infrastructures like the Hellinikon international airport in Athens (Greece) or the DMC factory in Mulhouse (France) and a vacant network of underground bunkers13 in London (UK).

%20(840%20x%20412).jpg) Sesena (image: Aurélien PIC)

Sesena (image: Aurélien PIC)

An investigation of the latent potential of modern ruins…

Adopting Bourdieu’s14 understanding of the forms of the capital, we support that modern ruins have persisted in their being long enough to carry social and cultural information embedded in their physical appearance and functional use. They also hold either explicitly or implicitly an architectural and aesthetic value generated by their fragmented and decayed appearance. Not only are parts of a wider ‘historic urban landscape’15, but their embodied cultural capital also manifests itself through the collective memory. Settis wrote that ‘trauma and discontinuity are fundamental for memory and history, ruins have come to be necessary for linking creativity to the experience of loss at the individual and collective level. Ruins operate as powerful metaphors for absence or rejection and hence, as incentives for reflection or restoration’16. However, in the face of global economic crisis, immigration and the mass displacement of refugees, modern ruins have now more than ever the potential to be formally or informally rehabilitated to serve more inclusive and sustainable social and spatial outcomes.

%20(840%20x%20630).jpg) Abandoned Hellinikon airport (image: authors' personal archive)

Abandoned Hellinikon airport (image: authors' personal archive)

Rehabilitating and regenerating decayed buildings and sites is not a priori successful and the already implemented spatial approaches vary in scale, intentions and methods. Only within the last decades several proposals have been developed, from high profile urban redevelopment projects, like the Battersea Power Station or the docks of Isle of Dogs in London, to Occupy Movements, like the refugee settlement in the former airport in the city of Athens. Both instigating interesting debates on the future of modern ruins as well as the agenda of socio-spatial practices in contemporary Europe.

Effectively, modern ruins have served as an inspiration for several emerging artistic expressions in recent years and in relation to abandoned buildings and infrastructures. One example is the genesis of ‘Ruin porn’, which describes the pop aestheticisation of ruin and decay through photographic online blogs. Another trend is Urban Exploration (urbex/UE). Urban exploration, also known as infiltration, refers to the act of entering and exploring space debris; abandoned places, ruins or uninhabited sites. This embodied practice of reclaiming urban space has a strong contending character, since the access to these sites is usually under control or totally forbidden. Urban explorers, either as individuals or as groups, after selecting the site, they infiltrate into the place, document through photographs and sketches the whole procedure and publish online the collected material to establish an open dialogue with the broader community. In that sense, urban exploration can be considered as a political act, a denouncement of the quality of contemporary urban environment that is characterized by spatial and social exclusions, and of the way it is nowadays inhabited.

%20(840%20x%20630).jpg) World War II Bunker in London (image: authors' personal archive)

World War II Bunker in London (image: authors' personal archive)

…through emerging social practices: A 5 steps model to Activate Modern Ruins!

Drawing on our experience as urban explorers, architects and urbanists, we developed the proposal ‘Activate Modern Ruins’ to challenge the established presumptions over modern ruins and urban decay as well as to re-activate numerous unused spaces through social practices that engage with a spectrum of stakeholders. So, the project speculates over the potential activation of modern ruins through the following steps: (1) Explore (2) Save (3) Crowdsource (4) Render and (5) Debate the Ruin!.

The first step is to Explore the Ruin! We imagine this phase as an ‘Open call for Evidence’ meaning an invitation to urban explorers and researchers in various European cities to submit material in a form of short texts accompanied by photographs, collected objects, plans, visuals, panoramas, videos or scans of the various places. The aim is to map a number of known and unknown cases, document their material and immaterial conditions, and communicate these findings online.

%20(840%20x%20521).jpg) Battersea Power Station (image: Construction Enquierer)

Battersea Power Station (image: Construction Enquierer)

This leads us to the second step Save the Ruin! After two months of receiving submissions, a digital archive of the collected material will be set up. Unlike the findings of most researches that are rarely communicated to the public, our platform will disclose all information from the open call and make the documents publicly available. This way we promote open-access of information and at the same time we attempt to raise awareness regarding the urban phenomenon of declining built environments. The third step seeks to engage individuals, local communities, experts and non-experts with the process.

Crowdsource the Ruin! will use social media platforms to digitally expose the archived case studies and invite people to contribute with ideas and possible future scenarios. Crowdsourcing is a specific sourcing model in which organisations use contributions from Internet users to obtain needed services or ideas in our case. Our goal is to share the information and knowledge about these spaces and create a pool of visions concerning the activation of modern ruins. We hope to get the public involved in the process, give voice and provide agency to existing social practices.

%20(840%20x%20560).jpg) Occupytion of Hellinikon Airport (image: Simela Pantzartzi)

Occupytion of Hellinikon Airport (image: Simela Pantzartzi)

The fourth step addresses the professionals of the built environment, architects and designers in order to Render the Ruin! During this phase, architects will be invited to respond and deliver concrete suggestions on specific case studies based on the material produced during the previous steps. We title this phase the ‘Architects’ Echo’ as we would like to think of our discipline as a sounding board that receives ideas from the society and reflects them forward adding its own layer of expertise. The purpose is to ask architects to work with what the community wants and needs, and how these activities or non-activities could be hosted in existing built forms. The submission of design proposals by the invited architects is the final part in the knowledge-production process.

By this point, we will have enough material to share in order to Debate the Ruin! As a final step, we propose the organization of exhibitions that will present part of the digital archive and the architectural proposals submitted by the invited architects. Next to that, we also propose the organization of conferences on modern ruins, which will offer the opportunity to juxtapose and openly discuss the ideas generated from the crowdsourcing next to those produced by the architects.

.jpg) Ruinporn across the Internet

Ruinporn across the Internet

We believe that the value of this 5-steps proposal lies in three simple concepts. First, it makes use of digital media to open source information and involve the public and other stakeholders in the production of knowledge and acting in the city. Crowdsourcing is the most vital part of this for it commissions an undefined and heterogeneous group of volunteers. Secondly, it is not an one-off thing but rather a long-term process, which engages each time with different stakeholders and combines top-down with bottom up processes abolishing barriers between the architectural discipline and the public. Last but not least, being inspired by the ideas of Venturi, Scott Brown and Izenour17, we once again call for architects to be more receptive to the tastes and values of people. We argue that there is a lot to ‘learn from ruins’, not as an opposition to the avant-garde architecture, but more as a realisation that the future of architecture can be more pragmatic, tactical and minor. It is more sustainable working with the existing resources and infrastructure, rather than inventing or imposing new ones. It is more interested in having people involved in the process rather than projecting architects’ own authority. And as such we believe that the future of architecture lies in modesty: modesty in form, scope and cost.

%20(840%20x%20525).jpg) Found Objects in Urbex (image: authours' personal archive)

Found Objects in Urbex (image: authours' personal archive)

Read the selected idea Activate Modern Ruin!.

Notes

- Part of this project titled ‘Archiving urban decay | Reanimate modern ruins’ was exhibited at the Greek Pavilion #ThisIsACo_op in the latest Venice Architecture Biennale (2016).

- See http://activatemodernruins.tumblr.com

- Dillon, B. Fragments from a History of Ruin Issue 20 Ruins Winter 2005/06.

- Edensor, T. 2005. Industrial ruins: Space, aesthetics and materiality. Berg Publishers.

- Simmel, G. 1911. The Ruin (transl. by David Kettler).

- See for example Boym, S. 2007. Nostalgia and its Discontents. Hedgehog Review, 9(2), where she explains that reflective nostalgia in architecture ‘cherish a certain kind of ruinophilia in the public realm, a love and toleration for modern ruins that keep alive memories of destruction and of multiple contested histories and coexisting temporalities.’

- See for example Woods, L. article ‘Beyond Memory’ describing his ‘War and Architecture’ projects as an alternative approach to the traumatic experience of a city’s destruction. Available at: https://lebbeuswoods.wordpress.com/2012/03/22/beyond-memory/

- See for example Trigg, D. 2012. The memory of place: A phenomenology of the uncanny. Athens: Ohio University Press

- Harbison, R. 1993. The built, the unbuilt, and the unbuildable: In pursuit of architectural meaning. MIT Press.

- Antonas, A. 2007. Delaying Demolition, https://antonas.files.wordpress.com/2007/08/ruin.pdf

- Huyssen, A. 2006. Nostalgia for ruins. Grey Room (23), p. 6-21.

- See Harbison, R. 1993.

- See https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/whats-on/hidden-london/

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. The Forms of Capital.

- The term and concept of the ‘Historic Urban Landscape’ was introduced by UNESCO in the 2005 Vienna Memorandum to promote a holistic approach in urban conservation practices.

- Settis, S. 1997. Foreword. In: M. S. Roth. Irresistible Decay: Ruins Reclaimed. The Getty Research Institute for the History of Art and the Humanities. Los Angeles, CA.

- Venturi, R., Brown, D. S., & Izenour, S. 1972. Learning from Las Vegas (Vol. 102). MIT press, Cambridge, MA.